Chiara Dellerba is an artist, facilitator and curator based in the UK. Her work explores critical, social and fictional dimensions of ecology, placemaking and conviviality. She often develops long-term collaborative and interdisciplinary projects that aim to expand notions of place, community and human- more than human relationships. Her Chimera Plantarium project investigates urban spontaneous plants, to map, rethink and redesign public places from the perspective of “weeds”.

The Chimera Plantarium: shaping worlds in urban wastelands

In his book Extreme Cities, Ashley Dawson contends that while cities are the largest contributors to climate change, they are also the most potent arenas for social transformation. Cities, with their dense populations and complex infrastructures, are simultaneously dependent on nature and capable of shaping it. This paradoxical role makes them ideal laboratories for testing large-scale ideas and exploring the potential for concrete impacts in mitigating what Dawson calls the impending “climate chaos.” However, this perspective also underscores the Anthropocene’s central limitation: the assumption that humans are the “lords” of the planet, an assumption that not only crushes us under the weight of our environmental impact but also engenders feelings of helplessness in the face of climate catastrophe and social inequality.

To counter this, we must move beyond the Anthropocene—a period marked by human dominance and environmental degradation—and adopt a more holistic approach that sees life on Earth as a complex, interconnected web with no hierarchical structure. This shift in perspective requires us to enter into what philosopher Rosi Braidotti calls “life among the species,” where we seek an escape from the paralysis induced by dystopian visions of the future and instead imagine a new post-humanistic morality. This new morality would emphasize cooperation, mutual relationships, and the recognition that all life forms have intrinsic value.

The Chimera Plantarium was born based on these premises and with the urgency to respond on a local scale to questions like: how can we rethink our relationship with nature? Can we start from our surroundings to slowly expand our trajectory to a wider scale? What sustainable practices can we adopt to ensure long-term impact? What if we move away from the conventional, manicured, and anthropocentric views of nature to celebrate and learn from urban wastelands?

It is in these neglected spaces, hidden within the city, that spontaneous flowers and adventurous plants, often dismissed as weeds have their home. These plants, creeping between cracks and fissures in the urban landscape, defied the constructed order and thrived in conditions where human intervention had failed. Weeds, often reviled as the antithesis of human struggles revealed themselves to be nature’s most resilient agents, persisting despite our efforts to eradicate them.

My journey into understanding these resilient plants began before the COVID-19 pandemic, but it was during the pandemic’s constraints that I, like many others, began to view urban wastelands as miniature laboratories. These spaces became places where the spontaneous dynamics of urban nature could be explored and where we could reimagine our position within the urban environment. I became fascinated with how these plants, despite being constrained, neglected, and growing in limited areas, continued to thrive. This resilience led me to investigate further, questioning the very notion of what constitutes a weed.

According to the Cambridge Dictionary of the English Language, a weed is any wild plant that grows in an unwanted place, especially in a garden or field where it prevents the cultivated plants from growing freely. However, naturalist Richard Mabey offers a different perspective, describing these species as nature’s repairers, plants that evolved to fill the empty spaces left by natural disturbances long before humans disrupted the landscape. Mabey’s work urges us to see weeds anew, as agents of repair, bridging the rift between humanity and nature. This idea inspired me to question whether we could include weeds in a broader discourse on repairing our relationship with nature.

Could we learn from these species about cooperation, resilience, and resistance against a culture that imposes a singular view of reality? Could we imagine urban spaces where these plants are not merely tolerated but embraced as citizens? Could we co-design with nature and involve weeds in this discourse? These questions and relative speculations have slowly defined what the Chimera Plantarium is: a collaborative laboratory of civic and ecological imagination.

The concept of the Chimera Plantarium draws from the mythological Chimera, a creature composed of multiple elements from different species. The Chimera, with hybridization at its core, embodies the idea of not being confined to a single category but forging strength through the integration of diverse species. With this concept in mind, the Chimera Plantarium proposes a new idea of citizenship—one rooted in learning from others, adapting together to changes, and embracing hybrid ways of being instead of opting for a monoculture of existence. The term “Plantarium” is itself a chimera word, combining “plants” and “planetarium.” It takes inspiration from Gilles Clément’s concept of the “third landscape,” which posits that we, like plants, are gardeners of the Earth and that on a planetary scale, we can co-design the thriving of multiple species without hierarchy.

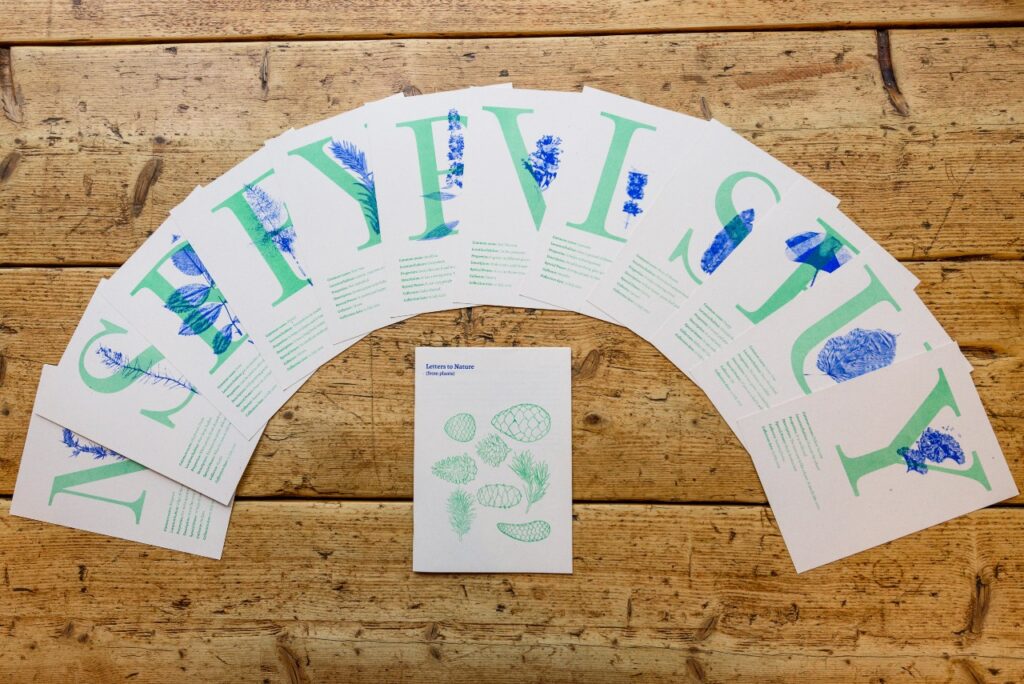

With this in mind, the project usually starts with mapping marginalised spaces and exploring their potential. The interaction with these spaces, often neglected, can take the form of diverse forms of engagements, usually hybridised, interconnected and in a continuous evolving: local collaborative maps in the form of herbariums, communication campaigns as colourful murals, foraging walks, and performative workshops. Slowly they became not only places of biological invention but also of social and civic imagination. These areas, in their abandonment and indecision, become welcoming havens for diversity. They are neither purely wild nor entirely human-made but occupy an interstitial space where something new can emerge.

With this in mind, the project usually starts with mapping marginalised spaces and exploring their potential. The interaction with these spaces, often neglected, can take the form of diverse forms of engagements, usually hybridised, interconnected and in a continuous evolving: local collaborative maps in the form of herbariums, communication campaigns as colourful murals, foraging walks, and performative workshops. Slowly they became not only places of biological invention but also of social and civic imagination. These areas, in their abandonment and indecision, become welcoming havens for diversity. They are neither purely wild nor entirely human-made but occupy an interstitial space where something new can emerge.

Lately, reflecting on Anna Tsing’s book The Mushroom at the End of the World, I was particularly struck by her notion that “watching landscapes in formation shows humans joining other living beings in shaping worlds.” These landscapes, she suggests, can be radical tools for decentring human hubris. Tsing’s insights pushed me to further question the status quo of our relationship with urban greenery and the hierarchical structures that define it. The Chimera Plantarium, therefore, is not just a project; it is a call to rethink our position within the urban ecosystem and to imagine a more inclusive and collaborative future for our cities, where even the humblest weed has a role to play.

Images:

Heading: still from On Hannah Fields, Lewis Heriz

The Chimera Plantarium, Fermynwoods Contemporary Art, Corby, 2022 Photo: James Steventon

Herbarium and Letter to Nature (from plants), The Chimera Plantarium, Primary, Nottingham, 2020 Photo: Tom Morley